![]()

Forty Years Later with two Old Testament Dudes

On Dewey Whitwell's Knee, I Consider My Second Amendment Rights

![]()

"Jan Worth published her great novel Nightblind herself (with iUniverse) and thank goodness she did. She worked on it for about thirty years she says in the Acknowledgements.

Worth’s book is splendid and delightful, wise and witty and rich. Twenty times better, say, than something like Eat, Pray, Love...." (Read the full review...)

![]()

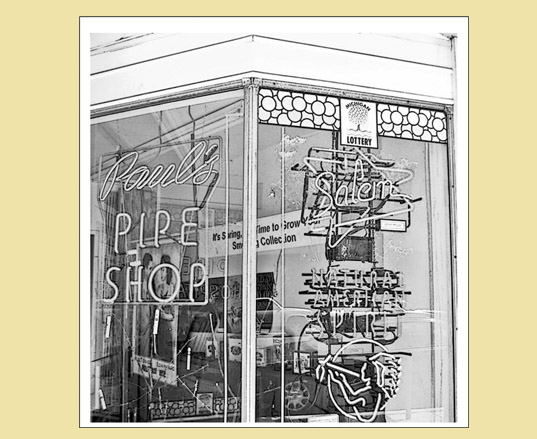

Essays > The Pipe Saved This Flint Man's Life: Here's Why

“The pipe saved my life.”

So begins Paul Spaniola, legendary owner of Paul’s Pipe Shop at 736 South Saginaw.

He has just turned 95, and though he sometimes struggles to find the right word and complains that his brain doesn’t work as well as it used to, his eyes are bright and his zest for telling stories of his life as a fiercely persistent downtown businessman is fresh and undiluted. Political correctness doesn’t deter him – he knows what he knows.

“I’d just turned 40,” he recalls, picking up the tale, “and I had three heart attacks in one year. I lay in bed in the corner of my old house for three months and I got sick of it.

“So finally I gave up and went to Peerless – it was right across the street from my store back then – and I bought a new recliner. I said to myself, ‘If I’m gonna die I’m gonna do it right in this chair.’ So I put it in the back of the store and laid back there and smoked my pipe. “

For months, some say years, he waited on customers from that chair, keeping calm by smoking a pipe. It was usually a Cayuga, the briar and Lucite pipe he makes himself. The pipe tasted good, he said, and the pleasure of it, the serenity of it, he believes, kept him alive and healed his heart.

That was 55 years ago, and Spaniola says his doctor tells him his heart is okay. He still smokes a bowl of his own blend, which he describes as a mix of chocolate and vanilla, once a day. He’s never had heart surgery.

“You don’t smoke cigarettes, do you?” he demands in the first moments of our interview. “If you do, get off of them. It’s terrible for you. Smoke wasn’t made for your lungs. I never inhaled. You should never inhale.”

While he still goes into the shop once a week or so, where his son Dan and daughter Janice Caudle keep things going, for our conversation on a wintry Tuesday, he’s requested we meet at his kitchen table in his cozy brick house in Swartz Creek. His daughter Pat Schoenfield bustles around, bringing out a fat scrapbook and making sure we’re off to a good start.

He proudly talks about his twelve children, all with first wife Leona. Two died as children and two others died later, but eight remain, along with 82 grandchildren, 83 great-grandchildren and three great-great-grandchildren. Leona died after 46 years of marriage. His second wife, of 26 years, Doris, died late last year.

Paul’s Pipe Shop has been a fixture in downtown Flint since 1947, but Spaniola’s business career began two decades earlier. When his brother Roy started a tavern and pool hall in Swartz Creek in the late Twenties, young Paul rode his bike in from Owosso to hang out and make extra money shining patrons’ shoes.

Later, Roy joined the Marines and Paul took over the bar. He had a knack for repairing pipes, and eventually bought his brother out. He renamed the tavern Paul’s Pipe Shop and Pipe Hospital. Encouraged by a lawyer and judge whose pipes he repaired, Spaniola dropped the liquor part of the business and moved into Flint, first in Buckham Alley and then on Saginaw Street. To his astonishment, the pipe business flourished.

A series of crucial developments shaped Spaniola’s success. First, through persistent trial-and-error, operating in secrecy, he learned how to make a pipe. His Cayuga brand, boiled in oil and cured in what he elusively calls “miracle cake” gained an international reputation and continues to be sought out by pipe smokers around the world.

Asked for specifics about the oil process and “miracle cake,” Spaniola clams up. The recipe? He points to his head. “It’s in here,” he says, smiling cagily. “And my son knows.”

Second, Spaniola developed several idiosyncratic blends. Arrowhead, named for his hometown of Flint, along with 2120, Flint Mix and SPEG continue to find a market locally and around the country.

Third, Spaniola and fellow pipe aficionados started a pipe-smoking club, and for fun, initiated yearly pipe smoking contests. At its peak one year, the competition drew 145 smokers, including 34 women, and attracted international attention.

“Some of the women threw up,” Spaniola recalls. “Maybe they inhaled by mistake. Pipe smoking isn’t for everyone.”

The rules are fixed: each smoker receives exactly three and three-tenths grams (one teaspoon) of tobacco and two matches. Each contestant has one minute to get the pipe lit, and then the contest– how long can a smoker keep that tobacco going?

Spaniola himself won six times, in 1951, ’66, ‘ 70, ’73 and ’92, when he was 79 years old. His record is one hour, 38 minutes and 53 seconds.

UM – Flint Writing Center Manager Scott Russell is one of many pipe smokers who entered the contests in the Eighties. He remembers with amusement one event held (in obviously very different times) at the Prahl Center at Mott Community College.

“We all thought pipe smoking was cool – we thought it made us look like intellectuals,” Russell recalls, “So I thought I’d see if I could compete.

“There were all these old guys walking around demanding ‘make smoke!’ and if you couldn’t, you were out,” he recalls. “You’d hear all these sucking noises but if you couldn’t ‘make smoke,’ you were sunk.”

One of those “old guys” was Charles Stewart Mott, a devoted pipe smoker and head of the Mott Foundation. He stopped by the pipe shop frequently and he and Spaniola became friends; Mott had Spaniola send his tobacco and Cayuga pipes around the world to various friends and associates.

“How it started was, I called the Mott Foundation to see if he’d participate in one of the contests,” Spaniola says. “At first they wouldn’t put me through. I kept asking for just five minutes.

“Finally, I got through and I said, ‘I know you’re Mr. Mott and I know you’re Mr. Flint and I know you smoke a pipe and I’d like you to judge our contest.” Mott agreed, and after that showed up as time keeper almost every year.

Mott even donated one of Spaniola’s most cherished keepsakes – a Meerschaum pipe he was given on his 1897 graduation from Hoboken College in New Jersey.

“I said, are you sure you want to give this to me? You have two sons,” Spaniola recalls, “but Mott said, ‘ah, they’re not interested. They smoke cigarettes.’ I love that pipe. I wouldn’t sell it for two million dollars.”

That pipe is one of “about a million” pipes Spaniola has collected over the years – a collection that he calls his “pipe museum.”

Spaniola’s “piperitis,” as he puts it, also put him into contact with several celebrities – he and Arrowhead Pipe Club member Max Agree, for example, once appeared with Dave Garroway on the Today Show.

One of his favorite stories is how he met the actress Susan Hayward. At a pipe convention in Long Beach, CA., Spaniola was hailed to 20th Century Fox. A producer wanted an expert to teach Hayward how to smoke a corncob pipe for the 1953 movie “The President’s Lady,” co-starring Hayward and Charlton Heston.

Accompanied by four buddies from Flint, Spaniola waited for Hayward for hours, hanging out at the commissary where they rubbed shoulders with Doris Day and other stars. Hayward called in that her dog had bitten a neighbor’s kid and everything dragged on and on. Finally, she showed up.

She was a quick learner, but Spaniola was disappointed by her lack of star quality.

“She was just a little red-headed girl with lots of freckles,” he says with a smile. “You never saw those freckles in the movies.”

A press agent joked that Hayward should be careful around Spaniola: “He has ten kids, you know.”

Spaniola said Hayward turned to him and suggestively purred, “Well, I figured you must have done something else besides smoke a pipe.”

In 1998, former Flint Mayor Woodrow Stanley gave him a key to the city, but Spaniola was unimpressed.

“It don’t fit nothing,’” he wryly cracks.

Nowadays, Spaniola’s life is quiet and sometimes a bit lonesome. He misses his wife. “I’m just an old fool,” he says, “I sit around here all day until at night my kids come over and put me to bed.”

But every evening, he unwraps a pipe he’s been enjoying for 25 years from its felt envelope. He fills the bowl with his homemade blend, and meditatively smokes.

“I think about my life and how I first got started in business,” he says. “I think about how I got to where I loved the pipe. And I still love the pipe.”