![]()

Forty Years Later with two Old Testament Dudes

On Dewey Whitwell's Knee, I Consider My Second Amendment Rights

![]()

"Jan Worth published her great novel Nightblind herself (with iUniverse) and thank goodness she did. She worked on it for about thirty years she says in the Acknowledgements.

Worth’s book is splendid and delightful, wise and witty and rich. Twenty times better, say, than something like Eat, Pray, Love...." (Read the full review...)

![]()

Essays > Art for Stepping Into the Fire

This month I’m starting my seventh decade. If the Biblically-allotted three-score and ten bears out, I’m down to the ten. It’s a bit shocking.

I’ve been experimenting with calling myself “60” for several months, but it still feels as if that ancient person with my name is somebody else.

Nonetheless, my left brain and the calendar tell the truth: I really was born in 1949.

According to family tradition (most of the principals are dead now, freeing me to embellish as needed), my mother went into labor after hitting a high note at choir practice at a little church in Ohio where my father was pastor.

Her labor, her third, was quick and easy and I was lifted out into the world by Dr. Homer Keck, a beloved neighbor and friend, before midnight. I’d like to think the rest of the choir – not exactly a band of angels, but a motley well-meaning bunch, were still singing. They were supposedly delighted by the fact of the preacher’s new baby, and I was born into an atmosphere of hope and joy.

There’s no way to know if any of this is true, but I’m grateful music – enthusiastic and a little off-key – was part of the hours just before my birth. I was born into music and art – albeit their religious branch -- and I have needed them later, when hope and joy, inevitably complicated by other realities, faltered and got harder to claim.

It’s art and music to which I increasingly find myself returning as I get old. I’ve recently rediscovered Bach’s Brandenburg Concertos, for example, and I’ve been avidly absorbed by the spiraling, gorgeously complex movements loaded on my iPod as I walk the neighborhood. It reassures me: humans are capable of creating order and transcending evil.

And on a recent Friday afternoon, I had a chance to meander once again through the galleries of the Flint Institute of Arts. I cherished the pleasure of doing so with Kathryn Sharbaugh, the FIA’s assistant director of development and a fine teacher and ceramicist. As she told stories about the collection, I was touched anew by the power of two particular pieces.

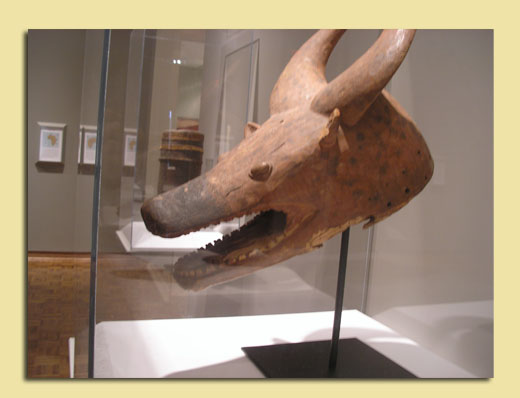

First is a mask in the African art gallery. It’s from the Guro tribe of the Ivory Coast, and was a gift to the FIA from Justice G. Mennen (“Soapy”) Williams. It’s roughly a water buffalo, a feral, dog-like head with horns, jagged teeth and protruding, primal eyes. Sharbaugh said it was worn for ceremonial occasions – often to dance for rain.

What captivates me is the creature’s snout. Three or four inches up, it’s roughly coated with black ash. Here’s why: Sharbaugh said to get the gods’ attention, the dancer would sometimes walk right into the fire, dipping the mask into the flames.

That smoky snout stuck with me. At first the gesture of dancing into the fire seems reckless, even ignorant.

But who among us hasn’t had our trial by fire? And who among us, for that matter, hasn’t sometimes chosen to walk right into the heat of desperate action because there is no other way?

The Guro mask gripped my heart, the human condition opening up like a full moon, and I felt less alone. Those Ivory Coast dancers know something I am also learning, and if I’m lucky I won’t forget it as I get old.

Then, in the Asian art gallery, a set of five pieces that on their surface couldn’t be more different from the Guro snout. What caught my eye, by an unknown Chinese artist of the Qing dynasty, was an incredibly delicate “desk set,” as Sharbaugh described it, likely for a Buddhist calligrapher.

The three vases, an incense burner and a brush washer date to the mid-18th century. They are porcelain flawlessly fired with a celadon glaze, a serene pale green.

One vase has rare parrot handles; a dragon adorns the brush washer. Sharbaugh says the five items are among the most valuable in the FIA collection. Three of the five were a gift from Thelma Foy, the daughter of Walter Chrysler. She grew up in Flint before her father got into a tiff with Billy Durant and moved the family – and his auto business – to Detroit. As an adult Foy fell in love with Chinese porcelain and collected a number of rare pieces. Remembering her childhood home with fondness, she donated them to the FIA.

Two things struck me about the porcelain desk set. First, as tools for creativity they acknowledge the need for peace, order and beauty. When the artist sits down to work, often struggling with difficult material, it helps to have something lovely nearby – we need, after all, to believe in beauty. Each vase in the set is for a different flower, a different season. It seems to me we need reminders, too, that hope comes in cycles and sequences, and that as Goethe said,“nothing is worth more than this day.”

Finally, the celadon set is an artifact, startlingly, of violence. These pieces and others like them were so coveted that people killed, stole and kidnapped for them in trade battles, called the Ceramic Wars between China, Japan and Korea that extended over several hundred years.

So people went to war for beauty? You could say so, Sharbaugh said, and it went on and on.

Sigh. On one hand, the idea that people would care so much about beauty that they’d fight for it almost seemed admirable, a notion from a long-past time.

Of course it was really about power – beauty almost lost in the battle for ownership, the way people in other times have gone crazy for tulips, and water rights, and land. We seem to struggle mightily to figure out what’s worth fighting for.

Thus the fact that these five pristine pieces survived without a single chip, their pale aqua glowing behind glass at the FIA , is stunning.

And I keep thinking of the calligrapher, hundreds of years ago, sitting down each day at his table. He savors the fresh chrysanthemum in his parrot vase, breathes in fragrant air, and gets to work, knowing that there might some time be the need to stand up and walk into the fire to fight for the beauty of the world.

And that’s what I hope to do -- for at least the next ten years.